Common misconceptions about the complexity in robotics vs AI

So now that the International Conference on Robotics and Automation(ICRA) 2024 is over, maybe it’s finally time to finish up my thoughts around the difference of the problems we are faced with in robotics vs AI research and to shed light to that difference and some misconceptions. This post is mostly catered to tech-people, but I kept it light-hearted and general so I can send it to my friends. I will mention a little bit about the current (2024) advancements later in the text, and that part might be a bit more technical.

Background

As I work in robotics research, I’ve often had to explain the difference between Robotics and Artificial Intelligence (AI). The two fields have obvious overlaps, but as things have developed, especially recently, there’s more difference even in the methods of automation. In the public perception, those two fields are often seen as equivalent.

When people talk about AI threats, this is the face they often imagine.

When people talk about AI threats, this is the face they often imagine.

With the reignited discussion surrounding AI due to the recent advancement in large language models (LLM) such as ChatGPT, I’ve had to explain the difference more often. A recurring question has been “While AI(LLM) have made such rapid progress, why haven’t robotics? How hard can it be to create a brain for a robot now that we have ChatGPT?”

My face after getting that question for the 26th time

My face after getting that question for the 26th time

The main point I have to repeat is the argument that sensorimotor task is harder than what you think, and that the advancement in LLM does not directly transfer to some robot sensorimotor task performance(yet). In layman’s terms, I always have to start by saying “Everyone equates the Skynet with the T900 terminator, but those are two very different problems with different solutions.” while this is my personal opinion, the latter one (T900) is a harder problem.

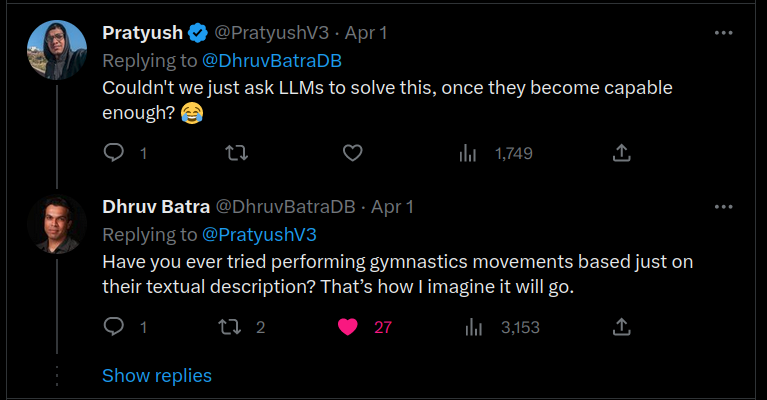

So I decided to write down my thoughts and some arguments for it so that I can just refer to this post later on. This post will be aimed mostly towards people with more tech/science leaning. The specific perception I want to address can be summarized in this (now deleted) reply on Twitter to a professor in robotics posting his work

LLM-bro on Twitter replying to a professor in robotics that tweeted his new research paper.

LLM-bro on Twitter replying to a professor in robotics that tweeted his new research paper.

This post will be divided into 3 sections. First I’ll describe the (relevant part of) how current AI solutions works, then explain the difference in the problem setting for robotics and why the methods(solutions) in AI/LLM might not be enough to solve this, and finally I touch briefly about why I think many people have had hard time wanting to even accept a central point being made with some insights that come from this.

Keep in mind that a lot of things mentioned here are still something actively debated, with fair disagreements. So I might soon be proven wrong. Also, when I say the word robot in this post, I’m talking about a general-purpose robot, and not everything mentioned here applies to special-purpose robots.

How do the AI solutions right now work?(briefly)

Since the breakthrough of the group of algorithms/methods called Deep Learning around 2009-2012 in image and pattern recognition, a lot of the subsequent methods that have been developed fall into the same group methods. This includes the Generative AI class of algorithms, such as the now famous ChatGPT, all the AI synthesized voices and Image generation tools such as StableDiffusion, Midjourney, etc.

Without going into the technical details, there are a couple of factors that underpin these groups of methods. The first one is the computing power. The breakthrough in 2011 (AlexNet, DanNet) happened when people used Graphic Processing Units (GPU), a specific type of chip to dramatically speed up the training process of those deep learning models. The other is requirement for the massive amount of data. It started with tens of thousands of cat pictures to train a model to distinguish cats in the early 2010s to most of the freely available data on the internet to train the model to generate images or text. Richard Sutton wrote in his essay The Bitter Lesson [5] about how the rise in computing power is the driving factor of AI advancement.

Those two factors are important in our context. Compute and data are the main pillars of such methods. These are not the only factors, but the computation(power) and data requirements, especially the latter, are something to keep in mind in the context of robotics.

What is hard? What is complex?

Let me start by quoting Jacob Browning from this debate (timestamp 56:21) [3]:

In 1966 MIT Summer Vision project aimed to teach a computer to see in a three-month program. There was a broad assumption that getting a computer to use language and reason was the hard problem of AI. Perceiving, by contrast was thought to be simple, and nothing more than putting input into a cognitive system. This project failed. It turns out vision is really hard …… the historical background assumption underlying the vision project was the idea that cognition was essentially linguistics, and the corresponding assumption that non-linguistic processes like perception, action and motion and so on are all non-cognitive and easier to solve.

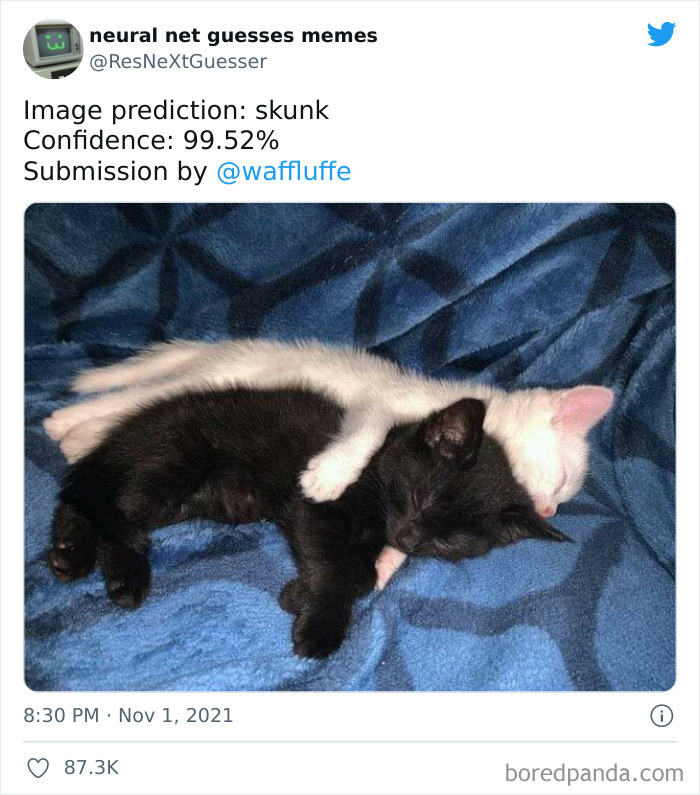

In layman terms, what he said was that people had the assumption that reasoning about things (such as cats) in a picture is a harder problem than finding out what part (pixels) of the picture are things (cats). However, it wasn’t until 2011 that we could somewhat reliably know what part of the picture are cats (and it still produces funny gotchas as below)

The point I want to emphasize with the above quote is that, our general intuition about the difficulty of a problem is often a bad metric for how hard it actually is. And we might be only partially wiser than what they were in 1966.

Known since the 80s

The above observation is not mine. In fact, it has been known since 80s and has a name: Moravec’s Paradox:

Moravec’s paradox is the observation by artificial intelligence and robotics researchers that, contrary to traditional assumptions, reasoning requires very little computation, but sensorimotor and perception skills require enormous computational resources. The principle was articulated by Hans Moravec, Rodney Brooks, Marvin Minsky, and others in the 1980s.

Moravec was saying that when you want to reverse-engineer (replicate) a skill, those skills that are below the level of conscious awareness are the harder problems.

Imagine trying to teach a kid to ride a bicycle, and compare it to teaching the same kid how to do a matrix multiplication. The first skill is something taught to a kid, sometimes before entering elementary school. The latter is taught in High school or above. When teaching, you probably start by breaking down each task to a set of steps to follow, or concepts to learn. But most likely, the steps or concepts you break it down to are not that helpful for the bicycle, but easy to follow for the latter case, even for a computer. The former has way more unconscious processes involved than the latter and often requires more trial & error from the kid to finally “grasp” or “get” how to balance the bicycle, push the pedal and steer the wheel, for no better term. Meanwhile, matrix multiplication can entirely be taught with sheets of paper (albeit a lot of papers, if you think how much math you need to learn to understand it).

Let’s think about how it would work for a common and daily task, like making a cup of coffee/. Let’s try to break down the task: “Pick up the coffee mug on the table and take a sip”. You can assume that you know where the cup is. You have to break down each step into movements, such as “move the right hand forward, with speed X or Y cm. Move index finger and thumb Z cm”. It’s a task you most likely can do even without paying attention to it (you can do it while reading this). It’s tedious, but to “picking up” should be quite straightforward to break down. Now, how would your solution change if I added other objects in the way to pick it? How would you grab it if it was empty vs filled to the brim (without spilling the content)? What if there was something on top of the cup? What if something sticky, such as honey spilled on the table was gluing it to the table? Your subconscious process can quickly and easily adjust to those settings, but you probably have to rewrite your sheet of “move commands” entirely each time the task is slightly altered. If you have a programming background, you might think you can add if and while loops in the mix and keep the rest of the sheet mostly unchanged. And that might work for a while, in controlled environments, but in the real world, the amount of variation quickly becomes overwhelming.

Now I asked you to break down that task into “movement component”. But in reality, to make a robot (with a similar shape to a human) do that task, we actually need to break it down to Contraction&extension and effort on each muscle in your arm. It might not seem like a big difference, but unconsciously all your “movements” are also somehow transferred to some form of desired force output in your muscles. “Move right hand forward”, how would you express it in muscle movement and strength? Robots don’t have muscles but joints and actuators, so instead of contraction & extension we express this in Force/Torque. When this force gets wrong, we can sometimes see funny behavior such as this robot falling over due to thinking it is holding the doorknob and applying the required force to turn it, expecting resistance.

Robot trying to open a door

Robot trying to open a door

The thought exercise also had one gotcha; You could assume you know where the cup is. This might seem easy, but if I asked you to estimate where the cup is on the table, relative to you, with millimeter or centimeter precision, that is quite a hard task!

Keep in mind that all this computation has to be done very quickly, and all the edge cases have to be identified (estimated) and then reasoned in a timely fashion. Pouring the coffee into the mug mentioned above, for example, if not done promptly, will lead to an overflow of coffee! And just as in case of bicycle vs matrix multiplication, doing this entire process with just language is underspecified.

I haven’t even touched upon the requirement to also design the mechanical system, only on the software side of the problem. So a common rebuttal to this (especially from Machine Learning people) is…

“The hardware is just not there yet”

This is another argument I’ve heard multiple times, albeit a bit less recently, from Machine Learning folks: the hardware capacity is not there yet to actually utilize the AI advancement. Definitely, the number one excuse you’ll hear from machine learning practitioners joining a robotics company. (Disclaimer: this argument is something I’ve had to debunk multiple times in my professional career when certain professionals tried to relieve themselves of responsibility, so this section might come off as a rant).

Here’s a video of a human controlling a robot.

Human remotely controlling a upper-torso robot for a convenience store application. Filmed around 2020

Human remotely controlling a upper-torso robot for a convenience store application. Filmed around 2020

This is a teleoperated robot I used to work with. It’s a very simple (and cheap) setup at its core. The robot targeted mass production so a lot of sensors were stripped and some parts replaced with less reliable but cheaper components. But even on this platform, automating the task below with AI is a very complex thing. Yet humans can do this effortlessly; with only vision feedback, a complete VR novice could do this task in a couple of minutes without damaging the robot. And more impressively, we can adapt to slight deviations without many issues.

This robot was available 5 years ago. Now there are even more complex teleoperation setups and robots such as 1X technologies (formerly Halodi Robotics) or Teleoperation with haptics feedback by Shadowhand, and at time of this writing the Tesla-bot, Unitree H1 and Agility robotics Digit, etc. On the academic side, a cheap yet efficient setup such as Mobile-Aloha can (with teleoperation) conduct quite dexterous tasks. So the hardware has already shown its capacity to do things, when operated by a human brain. It’s hard to claim that the “hardware isn’t there yet”, when you have this setup, with a limited set of sensors & cheap hardware yet it can conduct complex tasks when operated by humans. (Whether it is economically viable or not, is a different question)

Two robot hands trying to apply contact lenses on a toy frog (I think it’s a frog…?) 7x speedup from original, Teleoperated. Source: ALOHA

Two robot hands trying to apply contact lenses on a toy frog (I think it’s a frog…?) 7x speedup from original, Teleoperated. Source: ALOHA

So here’s what they actually mean when they say the hardware is not there yet:

“We do not have the hardware that has already collected a gigantic dataset the size of the internet with all the possible thinkable human tasks that are perfectly executed by a human, that have been labeled and collected noise-free, with high precision. Oh, and also computational hardware that can run a ChatGPT-sized model in less than 1 millisecond.”

This is true, and the closest thing we have is probably the Ego4D dataset by Meta. But if that’s the requirement for a functioning solution to be provided by machine learning then most of the work has already been done for you. Collecting data in robotics is hard. “Hardware not being there yet” is a convenient excuse. When multiple different (cheap) hardware platforms have shown to be capable of doing precise tasks when controlled by humans, but not with AI, it is a weak one.

Tangent point: do we need better hardware to learn?

The above point is that even with a limited hardware setup, when operated by humans it can perform useful & complex tasks. So the hardware limitation to execute a task is not the problem. However, it does not answer the question if the hardware is limiting what AI can learn. The above-mentioned humanoid robot, for example, doesn’t have the sense of touch, or when operated by a human, a sense of weight when objects are picked up. But we humans have learned those things through our lives, and when operating the robot through VR headset, can substitute those sensations and still control the robot just fine.

This is a question we don’t really know the answers to yet[3]. Some researchers believe we wouldn’t require any complex hardware (sense of touch, etc) and simply videos will suffice, while others believe that to learn a physical grounding, a useful understanding of how the physical world works, we need data from a physical embodiment (a robot) and interaction with the world, not just observation.

Opinion shared by Head of Meta research during a Facebook disscussion 20-12-2021

Opinion shared by Head of Meta research during a Facebook disscussion 20-12-2021

Personally, I’m skeptical of the stance that video or internet data would suffice. But this also depends on what the aim of learning is. For a humanoid robot that can do what we expect from a healthy adult, I’m skeptical. But for a simple robot that can walk around in a factory and do predefined tasks, maybe.

The factors that underpin AI advancement can’t be expected (yet) in robotics

As you’ve seen from the above hardware examples, there are real efforts to create hardware platforms for teleoperation. The assumption here is that just like Deep Learning worked thanks to scaling up data (internet-scale) of human demonstration (videos, images, texts, sounds), if we collect enough data of the robot doing a certain task, label it with a textual description, we can train a model that can learn abstract actions so that we can skip the “movement component” process we pondered on before, and the model can robustly perform tasks it hasn’t originally been trained on. The effort to create this model called Large Behavior Models (LBM)[8] is happening at different labs. I think Russ Tedrake and Toyota Research Institutes work is worth a mention, along with Google (previously Everyday Robots). The academic effort to create a dataset to train these models (RT-X) should probably also be mentioned.

I believe that these methods will get us far, and we will probably see more versatile & dexterous robots coming out from both industry and academic labs.

But this will probably fall short of the expectations that we have of robots. A System failure by a robot is often not tolerated to the same degree as LLM models. We can all laugh and still keep using ChatGPT or Midjourney when it gives the wrong answer or an image with a human having 6 fingers. But a slight failure of a self-driving car or robot electrician cutting the wrong wire and putting the house on fire is unacceptable.

Imagine having a robot like this with the failure rate of ChatGPT

Imagine having a robot like this with the failure rate of ChatGPT

The world is a more dynamic & chaotic place than the internet. Edge-case failures we see for language models are tolerable for use-cases on the internet, but those failure-cases are more prevalent in the dynamic real-world, and for robotics not ignorable. Replicating all those edge cases would be an arduous and long task for data collection.

Even at the current stage of things, it seems like the quality of the data collected matters more than the quantity for robotics. Which contrasts with the case of LLM models. For robotics, before we even discuss hardware, The data is the bottleneck. By bottleneck, we don’t just mean the quantity of it which is in the process of being addressed by companies & LBM efforts like above. The content of the data, in its variety and preciseness, also matters.

The other thing is the computation factor. ChatGPT and Midjourney can write you a letter, solve coding problems, paint you a picture incredibly fast, compared to humans. Yet the speed those models output their results are magnitudes too slow for what is required to dexterously traverse and interact with the real environment. Even if we could collect precise data for robots, at the speed of about 250 milliseconds (average reaction time for humans, our reflexes, are even faster[6]), can we with the current models deploy that at the required speed?

For example, let’s see the case: You’re holding a lunch tray at the cafeteria queue and someone bumps into you from behind. The entire process from recognizing what happened, to steadying your balance while holding that lunch tray horizontally so the content doesn’t fall out or tip over, is happening fast. This is a requirement that is currently quite hard to achieve for the LBM or LLM models.

Robots are probably amazed by our ability to keep a food tray steady, the same way we are amazed by spider-senses (from spiderman movie)

Robots are probably amazed by our ability to keep a food tray steady, the same way we are amazed by spider-senses (from spiderman movie)

It’s worth mentioning that this kind of balance problem is something some robot solves very elegantly. You’ve probably seen Boston Dynamics bullying their robots to show this capacity. These robots use entirely different methods, so it might be unfair to ask an LLM model to do this, and instead, we can figure out how to connect those methods. But that again is a tricky problem to solve, and probably outside of what we can expect from Deep Learning alone. How to connect that is also ambiguous. From the lunch tray example, we know that there’s some higher-order reasoning directly affecting the lower-level control of balance; if you bump into a toddler holding a lunch tray, he might over-focus on balancing his stance with his legs and drop/tilt the tray in favor of balancing his stance.

A lot is going on in your brain

A lot is going on in your brain

Meanwhile, your balancing system understands that holding the plate horizontally is also a high-priority goal. You will adjust your reaction very fast.

We take this for granted, but a robot that can’t address these surprises and gotchas in the real world will struggle to survive on the streets. Right now, there are enough obstacles to a street-ready “general purpose robot”

We need a more gangsta robot y’know? (generated with Stable Diffusion 2.1. The prompt did not include specifications about color of the robot, only the drip)

We need a more gangsta robot y’know? (generated with Stable Diffusion 2.1. The prompt did not include specifications about color of the robot, only the drip)

Why do we resist the idea that sensorimotor might be harder than abstract reasoning?

Ok so this section is all my personal non-expert speculation and I want you to take this with a bucket of salt. I added it for potential fun discussions.

When I mention that complex motor coordination tasks are harder than playing go/chess or writing code/math or even creative endeavors such as digital art, most people instinctively reject this idea. It is sometimes quite frustrating, reminding me of the comedy sketch The Expert because there’s often a bias that “because I don’t need to think about it when I do it, it must be easy”. The weird thing is that, even when I’m surrounded by people with expert knowledge, who understand the complexity of the problem I’m trying to explain, this point seems to not quite sit right!

My speculation is that the idea that some motor tasks are harder than what we as a society consider “high intelligence tasks” is an uncomfortable idea because it questions our belief in human exceptionalism.

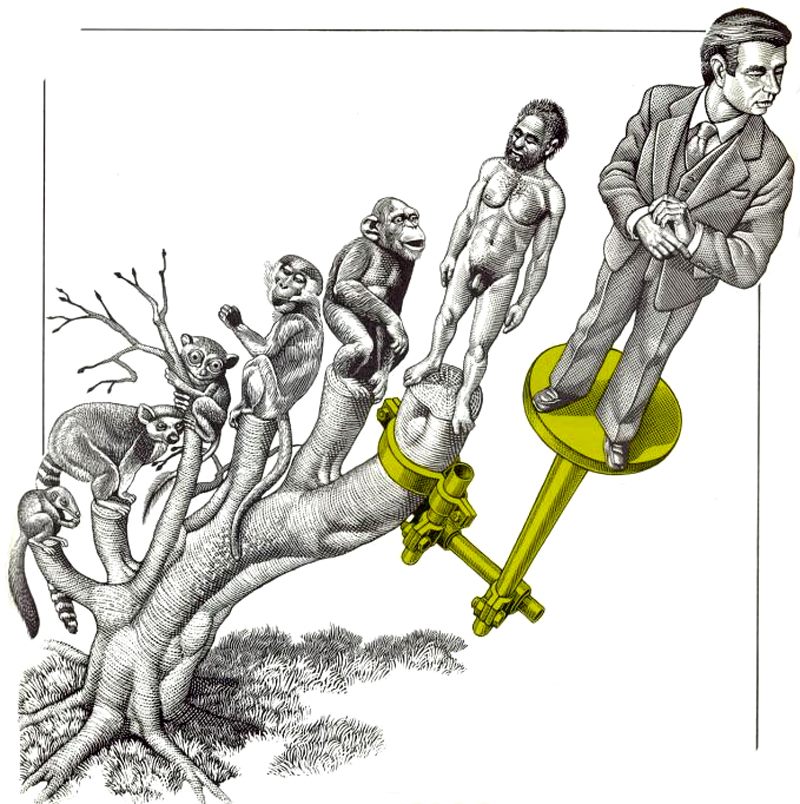

Illustration by Bill Sanderson, New Scientist, 13 May 1976

Illustration by Bill Sanderson, New Scientist, 13 May 1976

Motor coordination after all, to a certain level, can be done by animals. (Moravec hypothesized around his paradox, that the reason for the paradox could be due to the sensor & motor portion of the human brain having had billions of years of experience and natural selection to fine-tune it, while abstract thoughts have had maybe 100 thousand years or less.) Saying that these are more complex than abstract reasoning, for quite obvious ideological and religious reasons, doesn’t sit well with many.

It might not just be about human exceptionalism but also how our society justifies certain hierarchies. A white-collar desk worker typing in a spreadsheet is somehow seen as a more respectable and often high-paying job than trades jobs such as electrician, carpenter, farmer, etc. There’s an obvious economic reason for this, guided by supply & demand and other factors. But anyone that has worked at some corporate white collar desk job, with some form bullshit job must have thought at some point “Gosh, a monkey can do this” while being paid multiples of trade workers while effectively only doing menial tasks. Usually, these jobs also require a college degree from the worker (if not more). At some level, we need to create a cognitive dissonance to justify this. The point of sensorimotor tasks being harder than those years spent in college doesn’t really sit right.

Even early socialists thought domination distributed according to shares of intelligence was ok; from Socialism 1.0: The First Writings of the Original Socialists, 1803-1813:

I realize my friends, how entirely frustrated you are; but note that the possessors, although inferior in number, possess more enlightenment than you, and that, for the general good, domination must be distributed according to the share of intelligence.

Just for the record I’m not taking any moral stand on this. The reason why a society works a certain way is beyond my expertise. I’m just trying to point out examples of biases we inevitably have and when it comes to judging how hard a task is, might come to conflict; not so different from the mistaken observation researchers had in 1966 about reasoning vs perception.

It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it. - Upton Sinclair

I should also add that the complexity and utility of a problem/solution are not the same thing. Quite often in engineering and science, a very simple solution ends up having way more value than a complex one.

Final words

My thoughts around this subject first arose when I started to apply models from LLMs after some promising results I saw at the Conference of Robot Learning 2021. The result was promising, but like every roboticist can attest, the more you test a system the more you think about the limitations of it and the right conditions required to run it. The real world, unlike the internet where you and I mainly interact through text, voice, videos, is so varied, chaotic, and complex. But this is nothing new to someone who has tried to make a robot do something useful, so I didn’t bother to write it down much later, and the first take (2022) was way more tech-jargon heavy as it was for my own and often used as a base material to discuss with my coworkers, whose background was not robotics but machine learning and often neuroscience.

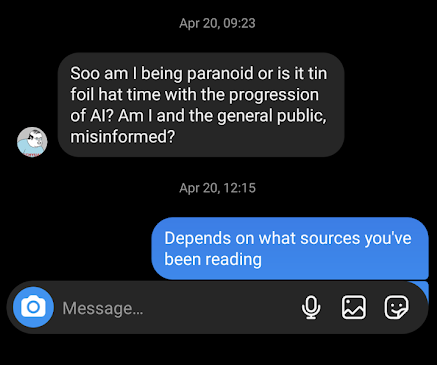

But after the release of Stable Diffusion (Image generation AI) and subsequently ChatGPT I started to get messages from friends like the following:

A message I got from a friend on instagram back in 2023 after ChatGPT was released

A message I got from a friend on instagram back in 2023 after ChatGPT was released

So I thought maybe this point of view is worth sharing, at least with some of my friends. After ICRA 2024 I also felt like this is a sentiment shared by a lot of robotics researchers. If you find it useful, or just fun, I’m glad it did but take it with a grain of salt. If you have constructive criticism I’m all ears.

To also add in case someone got the impression that I’m downplaying recent AI advancements, I’m not. I think the advances are remarkable, and I do think the impact they will have on our society will be big, both in positive and negative. My point is only that due to our skewed understanding of what is a hard problem to solve, people might extrapolate the current impact of AI development in the wrong direction and therefore get anxious more than needed for different reasons. Personally, I think the effect of Deep Fake and LLM-bot-based fraud, and the scale and ease of it will cause a profound change to the internet, society, and our culture. But my stance is similar to this post [4], that our culture will adapt to this new technology, just as it did before. But just as the 2013 self-driving hype didn’t live up to its promises (yet), I’m not sure the current hype will either.

As my ex-coworker, now a humanoid-robotics industry researcher said: The progress in (humanoid) robotics is remarkable, it reminds me of the speed of development of CPU. But a lot of it is driven by hype and an optimistic expectation of how AI advancement will transfer to (humanoid) robotics, and therefore I think the majority of the companies doing humanoid will not succeed in what they promised. But some might, and it might lead to iterative improvements that will slowly see them implemented more widely in society. Exciting times to be a robotics researcher!

Unitree presentation ICRA2024.

Unitree presentation ICRA2024.

Thank you Rousslan Dossa for helping me proofread it, it would’ve probably looked like an unreadable rant full of spelling errors otherwise.

If you want a more technical, serious (better) post with a solution oriented point to make, I’ll refer you to Eric Jang’s post [1]

References

[1] Eric Jang - How Can We Make Robotics More like Generative Modeling?

[2] Sarah Constantin - What does the cerebellum do anyway? (Note: I’ve been told by my neuroscientist coworker to take the claims in this post with a grain of salt, so you should probably too!)

[3] Debate: Do Language Models Need Sensory Grounding for Meaning and Understanding?

[4] AI: Markets for Lemons, and the Great Logging Off

[5] The bitter lesson - Rich Sutton

[6] Know your spinal cord – The reflex pathways

[7] Debate3 Generative AI will make a lot of traditional robotics approaches obsolete.

[8] EI Seminar - Siyuan Feng & Ben Burchfiel - Towards Large Behavior Models

Appendix

Sidenote: Our brains and the division of conscious/unconscious tasks

As an example for us humans, we know that the brain is divided into regions with different purposes.

But on top of this cerebellum we’ve also developed an entirely different process for situations that require even faster sensorimotor coordination: reflexes. When you step on a lego (ouch), with your reflexes you withdraw your leg, without even thinking about it. But at the same time as you withdraw your leg, another reflex also tells your opposite leg to help stabilize yourself, so that you don’t lose your balance and fall over [6]. This sensorimotor coordination requires such a quick motion that your unconscious process in the brain is even too slow, and it happens in the spinal cord.

For people that are familiar with the work of Daniel Kahneman, known for his book Thinking, fast and slow he suggests a framework of dividing thinking processes into “System 2” for slower, more deliberate & logical thinking, and “System 1” for faster, instinctive, subconscious & emotional thinking. Most problems so far that have been solved with AI methods are from System 2. In Kahneman’s framework, one could explain Moravec’s paradox by stating that “System1” processes are harder to figure out.

Another analogous concept is in the conscious process of becoming an expert. Magnus Carlsen, world champion in chess said in an interview that most of the time, he just knows what to do, and doesn’t need to figure it out. If you’ve learned how to bicycle, or drive a car, or mastered any other skill, you’ve done this too. In the beginning you need to focus more, put a conscious effort, using your “System 2”, in Kahneman’s terms, until after enough repetition, it becomes effortless.

We might not have to design things according to how a biological brain does things. The solution for robots might look drastically different. Nevertheless, we need a solution to address those problems that will inevitably happen in the real world. Thinking that an AI model that can mimic parts of the human cognitive process, with all the aforementioned factors required to make it work, to be able to also solve these hard tasks, is an unanswered question.

For an interesting read about the cerebellum, the part of the brain that controls movement, I refer you to this piece (my neuroscience ex-coworker did tell me some of the results are exaggerated, though) What does the cerebellum do anyway?